4 hours ago

John Waters Reflects on the Word “Queer” in the LGBTQ+ Community

READ TIME: 4 MIN.

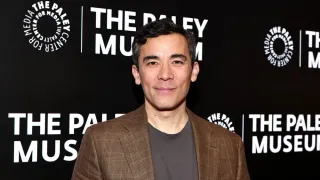

The word “queer” occupies a unique and contested place in the lexicon of the LGBTQ+ community. Once a slur, it has been reclaimed by many as a badge of pride and inclusivity, but its history as a term of abuse still resonates, particularly for older generations who experienced its sting firsthand. Filmmaker John Waters, whose work has long celebrated outsider identities, recently addressed this tension in a candid interview with PrideSource. Waters recalled that “it was very hurtful when I was growing up,” emphasizing the pain “queer” once carried for him and his peers. His remarks provide a window into the generational shift in attitudes toward the term and the broader cultural evolution of LGBTQ+ language.

John Waters, known for his transgressive films and unapologetic embrace of marginal identities, is no stranger to controversy—or to the power of language. In the PrideSource interview, he recounted how, in his youth, “queer” was “very hurtful,” a weapon used to ostracize and demean. This experience is shared by many LGBTQ+ people who came of age in the mid-20th century, when the word was almost exclusively used as a slur. Waters’ personal history with the term gives weight to his observation that its reclamation is both remarkable and, for some, still fraught.

Yet Waters also recognizes that language evolves. He notes that for younger people today, “queer” is not only acceptable but often preferred—a term that encompasses a spectrum of identities beyond the binary categories of gay and straight. This shift, he suggests, reflects a broader cultural movement toward inclusivity and fluidity, something he views as progress, even if it sometimes feels disorienting to those who remember the word’s darker past.

The reclamation of “queer” by the LGBTQ+ community is not a new phenomenon, but its mainstream acceptance is a relatively recent development. Scholars and activists trace this shift to the late 1980s and early 1990s, when groups like Queer Nation adopted the term as a political statement, embracing its outsider status as a source of strength and solidarity. For many younger LGBTQ+ people, “queer” is now a default identifier, one that signals openness to a range of non-normative sexualities and genders.

This generational divide is a recurring theme in discussions about LGBTQ+ language and identity. Older community members may still associate “queer” with trauma, while younger people often see it as a unifying, inclusive label. Waters’ reflections capture this tension, acknowledging both the progress represented by the term’s reclamation and the lingering discomfort it can provoke.

The debate over “queer” is part of a larger conversation about how language shapes identity, community, and visibility. Historically, LGBTQ+ people have been defined—and often stigmatized—by the words others use to describe them. The reclamation of slurs like “queer” is a powerful act of self-definition, but it is not without controversy. Some community members, particularly those from marginalized backgrounds, remain wary of terms that were once used to oppress them.

This tension is not unique to “queer.” Other terms, such as “dyke” and “fag,” have also been reclaimed with varying degrees of acceptance. The process is often messy and uneven, reflecting the diversity of experiences within the LGBTQ+ community. As Waters notes, even within minority communities, there are minorities—people who do not fit neatly into broader categories or who resist the labels imposed on them.

As a filmmaker, John Waters has long been attuned to the power of representation. His work, from “Pink Flamingos” to “Hairspray,” has celebrated misfits, outcasts, and those who defy societal norms. Waters’ perspective on “queer” is informed by his lifelong engagement with the margins of culture, where language is constantly being reinvented and contested.

In recent years, mainstream media has increasingly embraced the term “queer,” using it in titles of TV shows, academic disciplines, and advocacy organizations. This visibility has helped normalize the word, but it has also sparked debate about who gets to define its meaning. For some, “queer” is a radical statement; for others, it is simply a convenient umbrella term.

Waters’ own comments reflect a certain ambivalence about this process. While he celebrates the openness of younger generations, he does not dismiss the pain that “queer” once caused. His perspective is a reminder that language is never neutral—it carries the weight of history, memory, and power.

The debate over “queer” is unlikely to be resolved anytime soon. As language continues to evolve, so too will the ways in which LGBTQ+ people define themselves and their communities. What is clear is that words matter—they can hurt, heal, divide, and unite. John Waters’ reflections offer a nuanced take on this ongoing conversation, honoring the past while embracing the possibilities of the future.

Ultimately, the story of “queer” is a story of resilience and reinvention. It is a testament to the LGBTQ+ community’s ability to reclaim language, redefine identity, and challenge societal norms. As Waters observes, this process is not always comfortable, but it is essential to the ongoing struggle for visibility, acceptance, and equality.