November 19, 2007

Methodists reach out to the gays

Michael Wood READ TIME: 7 MIN.

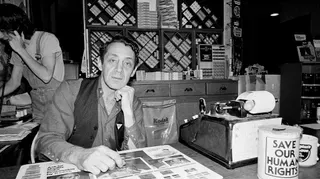

The Rev. Gil Caldwell is fond of quoting a character from the stage drama The Slave Narratives who said, "They use the Bible like a stick against us."

"They use the bible like a stick against us," Caldwell repeats during an interview in the chapel of Union United Methodist Church, an historically black South End church where he served as pastor from 1963 to 1968. The phrase would surface again during Caldwell's remarks at a banquet in his honor later that night.

"And tragically some persons, in their misinterpretation of scripture, have done that with Africans as they enslaved them. They've done that with African Americans as they segregated us," says the 74-year-old retired minister and civil rights activist, who grew up in the segregated South. Though the Bible hasn't changed, Caldwell observes that "some people are changing their interpretation of it and we need to acknowledge that." On the flip side, he adds, "for those who simply want to use the Bible as a stick or as a whip to control people, it's one of the most tragic distortions of that Word."

Caldwell sees little distinction between the ways in which the Bible was used to justify the oppression of black people and the way in which it has been used against the LGBT community. And that's why Union United's decision to cosponsor the symposium "Living a New Vision: The Struggle Continues!" along with The Church Within A Church Movement, a progressive, pro-gay group of United Methodists, is significant, said Caldwell. "The church has a long history of involvement in the racial justice struggle," Caldwell says of Union United, "but for it to also see the justice for persons who are LGBT is, I think, so very encouraging. And within the African American community the sad thing -- even in Boston -- is there are black clergy and black churches who don't seem to remember that the Bible was used like a stick against people of African descent, and in fact they are using the same kind of biblical [stick against LGBT people]."

While some black ministers and their churches in the Boston area have actively worked against the rights of the LGBT community, Union United Methodist Church has thrown open its doors to LGBT people. The congregation voted in 2000 to become a Reconciling and Inclusive Church, or one that advocates the full inclusion of LGBT people in the life the United Methodist denomination; it was the first predominantly black congregation in the country to take such a step. Last June, Union United marked another first for a predominantly black church when it played host to the Boston Pride Interfaith Service, an annual pre-Pride Parade worship service.

The Rev. Martin McLee, Union United's pastor, also acknowledged the importance of hosting the symposium at his church, which he noted happened with the congregation's approval. "I think one of the things that happens is, the progressive stuff that happens -- particularly with work that speaks to justice issues across divides and particularly including work in GLBT fights -- is that it often ends up being a fight where white folk are doing the fighting and you look around and there are no people of color," McLee observes. "And so I thought it was important to have it at a black church that's progressive in thought and that understands that God's love is inclusive love and not excluding love. So it was important for us to not just say that but to model it."

The Church Within A Church Movement is an organization of United Methodist clergy and laypeople that was founded in response the 2000 United Methodist Church General Conference, where the denomination voted to reaffirm church teaching that "the practice of homosexuality is incompatible with Christian teaching" and maintain its bans on blessing same-sex unions. "The desire was to create some kind of an alternative vision for an inclusive church ... for people who were getting tired of business as usual," said the Rev. Kevin Johnson, a co-convenor of Church Within a Church and the founder and pastor of Bloom in the Desert Ministries in Palm Springs, Calif. Church Within a Church is dedicated to being "the fully inclusive church" and promotes the creation of progressive congregations and ministry development, provides a pathway for the ordination of qualified gay people and actively works against racism - another issue with which the denomination, which was segregated until 1968, has long struggled. The group also provides educational and worship resources to progressive churches.

The symposium drew a racially diverse group of gay and straight United Methodist Church members as well as local elected officials state Rep. Byron Rushing and state Sen. Dianne Wilkerson to Union United to celebrate The Church Within a Church Movement's work and plot its future growth through a day of workshops and panel discussions.

"We are trying to grow the movement, we're trying to continue to inform people about Church Within A Church," said Johnson of the event. "But we're also trying to provide an experiential opportunity for people to see the values of working together [and] crossing boundaries in order to be a fully inclusive church that we all keep talking about," he added.

Caldwell sees little distinction between the ways in which the Bible was used to justify the oppression of black people and the way in which it has been used against the LGBT community.About 60 people registered for the symposium, which featured keynote speeches by the Rev. Dr. Traci West of Drew University Theogical School and Rushing. The Rev. Mpho Tutu, the executive director of the Tutu Institute, an organization dedicated to spiritual enrichment and the daughter of Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu, delivered the keynote address to a crowd of about 125 that gathered at the Back Bay Hilton afterward.

Church Within A Church's original motive for the gathering was simply to honor Caldwell for his decades of work on equality and social justice issues; the organization inaugurated the Gilbert H. Caldwell Justice Ministry Award in tribute to the minister and he was its first recipient at the banquet. But Caldwell, said Johnson, insisted that the gathering not completely focus on him, and that it also provide opportunities, i.e. the roster of workshops, for the group to do some work.

Though Caldwell tried to shift the focus away from him, it was clear that many at the conference relished the opportunity to gather in the minister's honor. West, who delivered the sermon at a Nov. 10 worship service, drew applause and "amens" from the pews when she stated, "At an event that's honoring Gil Caldwell you can talk about how persistent racism is in America, in the United Methodist Church and you don't have to tone it down.

"You can talk about how urgent it is to hold on to a vision of a fully racially inclusive, multicultural church where equality of our diverse God-created human worth is realized at every level," she continued. "You don't have to feel embarrassed for sounding na?ve ... and a little ridiculous for invoking a vision that is--"

"Like Jesus!" interjected a man in the pews.

West, an associate professor of ethics and African American studies, later drew murmurs of agreement and a knowing burst of laughter when she noted, "At an event where we are celebrating Gil Caldwell, we can talk about gay rights and the black freedom in America as thoroughly overlapping, thoroughly enmeshed, joined together -- goals and concerns and people -- without having to be conciliatory or apologetic to those who might not know that there are black gay and lesbian people ... that worked in the civil rights movement and still are around today."

Caldwell, who grew up in North Carolina and Texas, came to the city in the 1950s to attend the B.U. School of Theology. He was deeply involved in the civil rights movement in the 1960s, marching in the South and here in Boston, where as a vice-chair of the Massachusetts Unit of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, he helped organize a protest against the Boston School Committee's racial policies in 1965. Caldwell emceed a rally on the Boston Common that featured Martin Luther King, Jr. In recent years, Caldwell has become active in the struggle for LGBT rights both inside and outside of the United Methodist Church. In 2000, he co-founded United Methodists of Color for a Fully Inclusive Church, an organization that works for the full inclusion of LGBT persons at every level of church and society. He was also arrested at the United Methodist General Convention in Cleveland 2000 while protesting the church's anti-gay policies. Caldwell has also been a vocal opponent of state and federal anti-gay marriage constitutional amendments.

In his remarks at the banquet, Caldwell returned again to the theme of the Bible's misuse as a weapon of oppression. "I have African American brothers and sisters in the church who are using the same kind of methodology, the same kind of biblical interpretation to put down gay people that was used to put down black people," he said his voice rising to full-blown preacher mode. If it was wrong to use the Bible to enslave or segregate black people, said Caldwell, "then how in the name of heaven do we dare use that type of interpretation to somehow segregate or separate our brothers and sisters who are GLBT?"

And though Caldwell did not aim his remarks specifically at the predominantly white LGBT rights movement here in Massachusetts, he might just as well have when he said that desegregation is not a one-way street. Caldwell told the crowd that part of the reason he wanted the Church Within A Church symposium to occur in Boston and at Union United was "because I think it is important in this society, particularly [among] those who tend to be progressive, to give an understanding that desegregation is not one way." It's not enough, said Caldwell, "to simply want black folk and people of color to come to your organizations and make them 'our organizations,' and go to your churches." Rather, he said, "it's time for us to leave the comfort of our white zones, our white churches and our white places and go into some black places."

McLee, it seems, would welcome the help. Though he acknowledged being "hyped" and "excited" to continue his work on social justice issues, he acknowledged that it's difficult work. "It's painful and you have to deal with so much stuff," said McLee. "But this has been uplifting and joyous," he said of the symposium. "We've worshipped, we've celebrated, but it's not just worshiping to hear ourselves, it's worshipping to build the church, strengthen the church, nurture it, to reacclimate our engines so to speak. So I'm hyped because I know there's additional work to be done," said McLee. "But now I know a whole bunch of other folk with whom I can do the work. So I'm excited."

Michael Wood is a contributor and Editorial Assistant for EDGE Publications.